Black American Music

Posted: February 6, 2015 Filed under: Ken® | Tags: voicekwon 2 Comments »“It’s like a white person playing kayagŭm.”

Driving back from a show at a LA jazz club where the musician took care to identify as a Black American Music (BAM) artist, my sister and I were conversing about the performance when she drew a parallel between a white person playing jazz and a white person playing kayagŭm, a 12-string Korean traditional instrument.

Flabbergasted and absolutely incredulous, I yelled back that it’s not the same thing; white people can’t play Korean music without internalizing the essence of the music stemming from the lived history and sense of Han that Koreans collectively harbor from hundreds and hundreds of years of oppression under invasions from neighboring superpowers and colonialism. But it’s different with jazz!

“How is it different?” she asked.

…

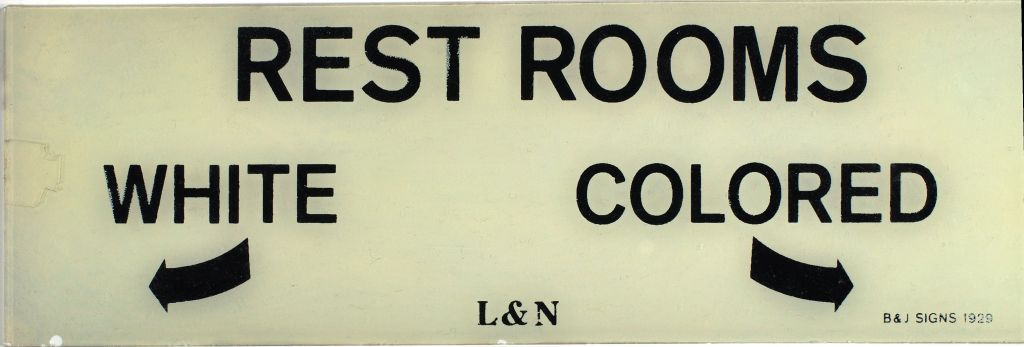

I tried to formulate my defense but began to realize that there wasn’t much to say. There was a time when jazz too was folk music, music rooted in a history and struggle, music that belonged to Black Americans. The difference is that Korean traditional music still very much belongs to Koreans whereas jazz has been appropriated to the point where I can forget about its origins if I’m not relentless about reminding myself. It’s pretty scary that I’ve been schooled in jazz for over a decade from my beginning at an arts high school to graduate school in a prestigious jazz program and had trouble seeing past a shallow revisionist account of jazz history.

Sure, we laughed in jazz history class about Paul Whiteman, the white man who was hailed as the “King of Jazz” back in the 20’s, but there was no real discussion on the politics of race and power and its influence on the music. Even when trumpeter Nicholas Payton started writing about and coined the term Black American Music on his blog, I understood his points on an intellectual level but didn’t care enough to thoroughly re-examine my paradigm.

I see now that this is not about jazz vs. BAM but about something that needs to be in the greater public discourse and has been with the much-publicized feud between Azealia Banks and Iggy Azalea. When my sister and I got home from the show, we grabbed In-N-Out and stayed up watching the interview below in which Azealia Banks articulates why she has a problem with Iggy Azalea, the self-described “runaway slave master,” becoming the face of rap/hip-hop. The segment on “cultural smudging” starting at 8:35 might be the best jazz history lesson I never received.

In Azealia Banks’ own words:

“Just in this country, whenever it comes to our things–like black issues, or black politics, or black music or whatever–there’s always this like undercurrent of kind like a f–k you, there’s always like a f–k you all ni–as, like you all don’t really own sh-t, like you all don’t have sh-t, you get what I’m saying?”

“So this little thing called hip-hop that I’ve created for myself that I’m holding onto with my dear f—ing life, it’s like, you know, it just feels like it’s being like, like snatched away from me or something.”

On the history of slavery and the lack of reparations:

“At the very f—ing least you owe me the right to my f—ing identity and to not exploit that sh-t, you get what I’m saying? Like, that’s all that we’re like holding onto, like hip-hop and rap.”

I think Azealia Banks must be one of the sharpest minds in popular culture. Fully aware of the long history of white people’s appropriation of black people’s creations and accomplishments as their own, she is vigilant about making sure that her genre doesn’t suffer a fate similar to jazz. I see now why Nicholas Payton wants to distance himself from jazz and be associated with Black American Music, a name that makes its origin clear.

@JAZZTOILET @AZEALIABANKS 🙂 Ha. Now you get it… Shout out to Azealia for speaking to White appropriation of Black culture. #BAM

— Nicholas Payton (@paynic) February 10, 2015

I can already hear some responding by saying “hey, it’s all about the music”—it must be nice to have that kind of privilege, to not have to acknowledge the issues. I’m willing to guess based on past experience that some of those same people would jump on the chance to profit from the injustice suffered by the communities of color under the guise of bringing the matter to attention or something like that. Here’s a good rule of thumb: it’s not okay to appropriate someone else’s suffering for your profit.

I’d like to point out one more thing that you may or may not have noticed. I’ve gone to over fifty jazz-presenting venues in New York City in my three years of reviewing bathrooms for this blog. Guess how many of them were owned by black people?

Zero.

Here’s one more quote from Azealia Banks on the upcoming awards that are supposed to represent artistic excellence in hip-hop, among other categories:

“When they give these Grammys out, all it says to white kids is–oh yeah you’re great, you’re amazing, you can do whatever you put your mind to. And it says to black kids–you don’t have sh-t, you don’t own sh-t, not even the sh-t you created for yourself. And it makes me upset.”

It makes me upset too.

In a relativistic sense…

Appropriation has very deep roots in white culture

Thought-provoking. And she’s totally right about all this. Unfortunately the American Dream is appropriately named.